National Football League vs. National Football League Players Association

Aug 11, 2022

Knowledge is a tricky thing and often develops a life of its own. It led to researching a subject I knew very little about. And all of this was made possible because Mom had this amazing talent of hanging onto documents, appreciating their historical significance and hoping someone would come along and discover these breadcrumb clues.

I learned many things about my parents while writing The Dutchman and Portland’s Finest Rose, none the least intriguing fact that Dad was the NFL player representative chosen by his colleagues to deliver a statement on their behalf in front of the Anti-Trust Subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee in July of 1957.

He never shared that important fact with my sisters and me. Nor did he discuss how his support of this fledgling association affected his treatment by the Ram’s front office while he was their starting QB. We were taught not to “toot our own horn,” and it was obvious he lived by his own words.

He never shared that important fact with my sisters and me. Nor did he discuss how his support of this fledgling association affected his treatment by the Ram’s front office while he was their starting QB. We were taught not to “toot our own horn,” and it was obvious he lived by his own words.

And once again, as with pondering what to do with Dad’s love letters written to Mom during their college years at the University of Oregon which resulted in The Dutchman, I’m left wondering what to do with these original documents. I care; does anyone else?

On November 1, 1956, as the NFL season was drawing to a close, Crieghton E. Miller, a retired NFL player and now acting attorney for three members of the Cleveland Browns football team, sent a letter to Norm Van Brocklin asking him to act as representative for his Ram teammates. Enclosed was a memorandum and authorization form requesting signatures of any/all players who might be interested in the formation of a “single, unified player’s organization.” It was stressed this information was “confidential,” and the following “suggestions,” were listed: “Certainly every player signed to a contract should be paid something for each exhibition game; there should be player representation in League meetings; the idea of pensions for players should be explored and the possibility of retroactive pensions considered; an annual game to raise funds for many of these programs would be a further possibility.” It was paramount that if any of these suggestions were to become reality, a majority of players from each team in the league would need to participate. At the time, there were 12 teams and a total of 370 players.

Things moved swiftly. By December 20, 1956, Bert Bell, then Commissioner of the NFL, was invited to attend a player’s meeting in advance of the annual player’s meeting scheduled for the Waldorf Hotel the following week. He declined. On December 28, 1956, the first Professional Football Player Association Meeting convened with the main issues for discussion: the structure of the Players’ Association; objectives to be decided at the meeting; and manner of presentation to Owners and Commissioner. Eleven teams were represented, the Bears being the lone holdout, and eleven team representatives were elected.

It was clear the U.S. economy was growing, broadcast radio and TV revenues were expanding, amusement taxes were reduced, and stadium attendance had increased, all financially benefiting the League and the 12 team owners. The players felt they needed representation to deal with the following issues; contracts, which were non-binding; injuries, which were not covered by health insurance; and minimum compensation for daily training camp expenses. The consensus from the meeting was that a “union” was not necessary, rather “we should be able to accomplish the same objectives by the representation system.”

On January 30, 1957, the National Football League Players Association made a public statement presenting Bert Bell with the following proposals for consideration by the league owners: formal recognition of the NFLPA and its Reps; a minimum salary of $5,000 for any selected player; a stipulated amount of expense money per week for vets and rookies during pre-season; a minimum of $12/day for lodging and meals during the period after training camp up until first league game, plus a minimum of $8/day while on the road; inclusion of an “Injury Clause” in all player’s contracts; and a shortened training camp period. By comparison, the average annual wage/salary in the U.S. in 1957 was $4,713, according to the Libraries of the University of Missouri.

Bert Bell dutifully presented these proposals at the annual owners’ league meeting, and to no one’s surprise, all were unanimously rejected. However, these proposals had gotten the attention of the owners, and very soon thereafter Bell started making the rounds in the halls of Congress on behalf of the owners. Miller, as legal counsel of the NFLPA, did likewise. And now the media was privy to the player’s concerns. It was clear by the letters going back and forth between the player Reps and Miller that sports media coverage was more sympathetic to the players cause than the owners.

It was imperative the NFLPA make a plea in front of the House Anti-Trust Judiciary Committee before summer training camp began. Miller made a reasoned case on June 12, 1957, and Van Brocklin made his statement in July that same summer. No immediate decisions were made legislatively that session, though it was acknowledged that the NFL was a business and as such might be subject to anti-trust regulations.

The handful of veterans, all in the waning years of their professional careers—Norm Van Brocklin, Kyle Rote, Y.A. Tittle, Bill Pellington, Bill Howton, Jack Jennings, Don Colo, Norb Hecker, Adrian Burk, and Joe Schmidt—stood to gain nothing, and indeed, gained nothing as they fought valiantly on behalf of the league’s younger players who were the future.

I discovered a priceless letter written by Pete Rozelle, Rams GM, addressed to Dad, dated June 12, 1957, just weeks prior to his House Judiciary Committee meeting presentation. I was struck by the language of thinly veiled threats, questioning Norm’s “intent” and “degree to which you must participate.” He went on to write, “I hope you will continue to give this whole thing a lot of thought and never reach a position wherein you can possibly hurt yourself as a player and in doing so hurt your team.” Not surprisingly, following his ninth season with the Rams, Norm was traded to the Eagles. Philadelphia was the worst team in the league and the only team he requested not to be traded to. Non-binding contracts only work one way.

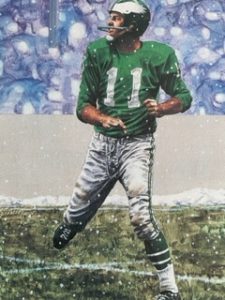

There was sweet justice, though. In three seasons with the Eagles as their starting QB, Van Brocklin took the last place team from the cellar to first and won the 1960 National Championship game, defeating the Vince Lombardi-coached Green Bay Packers. This was the only championship game Vince Lombardi ever lost, and Van Brocklin was named the MVP of the game. In October of 1959, Pete Rozelle became the new NFL Commissioner after the passing of Bert Bell while attending an Eagles game at Franklin Field. Rozelle and Van Brocklin’s paths crossed many times, and though often at odds with each other—I’d overheard more than one angry phone call between the two after games where Dad thought the officiating was sub-par—they remained brutally honest and worthy verbal sparring partners.

There was sweet justice, though. In three seasons with the Eagles as their starting QB, Van Brocklin took the last place team from the cellar to first and won the 1960 National Championship game, defeating the Vince Lombardi-coached Green Bay Packers. This was the only championship game Vince Lombardi ever lost, and Van Brocklin was named the MVP of the game. In October of 1959, Pete Rozelle became the new NFL Commissioner after the passing of Bert Bell while attending an Eagles game at Franklin Field. Rozelle and Van Brocklin’s paths crossed many times, and though often at odds with each other—I’d overheard more than one angry phone call between the two after games where Dad thought the officiating was sub-par—they remained brutally honest and worthy verbal sparring partners.

I wondered at the irony of how Norm could have played such an instrumental role in the creation of the Players Association and yet be so dismissive of it as a coach. Researching the history of the Association, I can appreciate how the original mission of establishing a “vehicle to discuss and resolve issues amicably” with the owners and commissioner had grown into something far bigger, more complex, and quite frankly, litigious. It is interesting to note that the Association has at times been a Union and at times not, changing to fit whatever legally was most advantageous to player demands. And, of course, as a coach, Norm found it hard to field a team when players are threatening or have gone on strike. I continue to be puzzled by his actions.

As long as there is sport, there will be this dynamic between players and both the owners and league they play for. So, maybe it was naïve of Norm’s generation to envision an association that could negotiate in good faith concerning issues of fair pay, health insurance, retirement benefits, a safe working environment, and shared profits. Who could have foreseen today’s league with 32 teams, legions of lawyers, agents, sponsorship endorsements, TV contracts, and guaranteed income for coaches and players that staggers credulity? Then, as now, players made a good income, and as Dad used to say, “I can’t believe I get paid money to play a game!”

It wasn’t until 1968 the NFL recognized the NFLPA. Ultimately the owners and the commissioner agreed to collective bargaining agreements.

Thanks to my friend, Bill Curry, former NFL player and past president of the NFLPA, for reaching out to the NFLPA on my behalf. I’m hoping there is some interest in these preserved original documents. They are living testimony of a rich history in sport and a window into the past. There is value in acknowledging those who’ve paved the future for this current generation. Do today’s football players care? I don’t know. All I can do is be a good steward and share what my parents entrusted to me.

History either matters or it doesn’t.

This is great stuff — essential Americana! Sports has become a huge industry, but there have, of course, been many other motivations (besides profit) over the years for their promulgation. I see Norm standing up for the individual participants and we don’t want to lose sight of the fact that one reason for sport is the participation and/or development of the individual (not to mention the development of individuals into teams). Then, as well, there’s the Labor – Management thing which has an essential American flavor (not totally comfortable), but which should be celebrated.

Thanks KC, I’m just now seeing this!